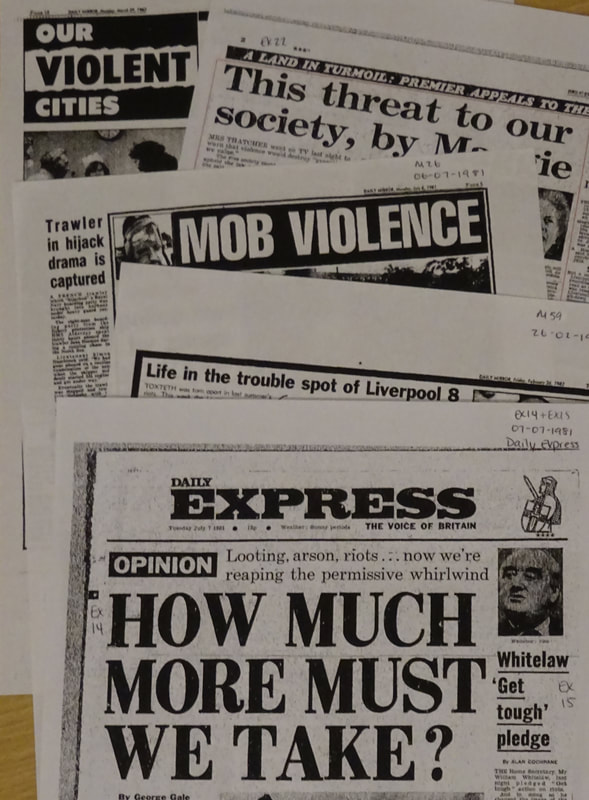

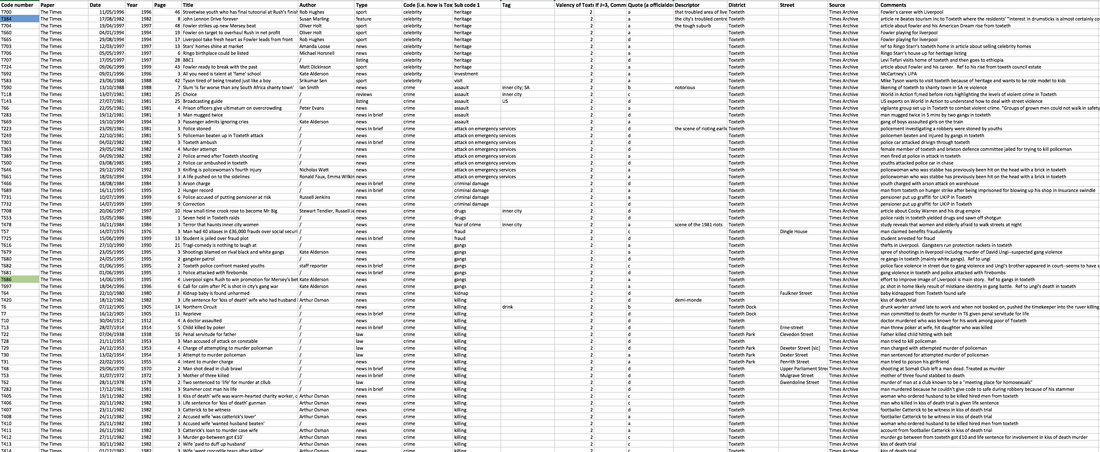

Alice Butler, School of Geography,University of Leeds Readers of this blog are familiar with a variety of practices used to analyse documents. This piece serves as a reflection on what is often seen as a confusing step in planning a textual analysis: creating a coding structure. I am a Human Geographer based at the University of Leeds where I am researching the historical formation of territorial stigma in relation to the district of Toxteth in Liverpool. Toxteth and Liverpool have a poor reputation (Boland, 2008) and Scousers—residents of Liverpool—are stigmatized particularly in the media where they are caricatured as being work-shy scroungers, morally degenerate and deviant (Boland, 2008). Liverpool is “synonymous with vandalism, with high crime, with social deprivation in the form of bad housing, with obsolete schools, polluted air and a polluted river, with chronic unemployment, run-down dock systems and large areas of dereliction” (Marriner, 1982 in Wildman, 2012: 119). Toxteth, a district to the south of the city centre, is particularly stung by a poor reputation with popular magazines and websites warning the public that Toxteth and its residents are dangerous; a popular men’s online magazine reporting that “shootings are a regular thing here, and pedestrians can almost certainly expect to run into trouble” (Clarke, 2009). I want to know how this pernicious reputation came to have such a grip on Toxteth. For this, I have turned to online newspaper archives and I have spent the last year scouring the Times, the Guardian, the Mirror, the Financial Times, and the Express archives from for the 20th century. I have completed a mixed quantitative-qualitative content analysis (borrowing heavily from the Critical Discourse Analysis tradition) of 1,950 newspaper articles that mention the term ‘Toxteth’. Putting together a coding structure can often be a daunting prospect and it is to that which I turn in the rest of this short piece. My coding schedule—the database into which the data and codes are entered—came about after a period of reflection: what did I want to find out through analysis? I wanted to know how the press stigmatized Toxteth in their coverage during the 20th century and, for this, I needed to note the appearance of certain words or phrases. I needed columns to hold the date of publication so that I could trace the use of these words or phrases over time. I needed to know who was quoted in articles and who was denied a voice, so I added columns for quotation source. Further, I wanted to mark whether articles portrayed Toxteth and events in Toxteth in a positive, negative or neutral manner, so I added a column for valency to reflect this. Finally, I needed columns to code for how Toxteth was mentioned in each article. This was the trickiest part of developing the coding structure as I had to develop codes and sub-codes that would reflect the content of the texts. A code is “a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data” (Saldaña, 2009: 3). It can be thought of as capturing the essence of data in much the same way as a title captures the essence of a book, film or poem (Saldaña, 2009: 3). In a quantitative study, codes are generally predetermined, separate from the text under analysis. In a qualitative study, the codes are “refined” during the coding and analysis process (Bryman, 2012: 559). For my work, I used a pilot study of regional newspapers that I didn’t include in my final analysis all available through the British Newspaper Archive, which helped me to determine some codes to be used in the main study, but I followed a qualitative coding approach that allowed me to generate new codes during the coding process. The codes, then, are generated based on what the text contains. For my research, I asked the question: in what capacity is Toxteth mentioned in this text? I allowed myself to develop as many codes as necessary in the initial first cycle of analysis (Saldaña, 2009: 3) and these codes covered everything from car accidents, race relations, and promiscuity, to community relations, deprivation, and drugs raids (see image below). It was at the second cycle of analysis that I condensed these codes and, for example, re-coded “burglary”, “robbery and “theft” all as “theft”. I also went back through the data and sorted the individual codes into “families” or categories (Saldaña, 2009: 8) that make the data easier to manage. Categories include umbrella terms such as “crime”, “riots”, and “politics” and the revised codes form the sub-codes within each category. Coding in this fashion can be a time-consuming and laborious process; this project took many months to complete. It is worth putting the time in to reflect on what you want the analysis of the text to reveal, and to spend some time conducting a trial or pilot study to test out an initial coding structure even if you intend to let codes generate during the analysis. However, the results are detailed and, if planned correctly, can provide a comprehensive way to understand texts. References Boland, P. (2008) ‘The construction of images of people and place: Labelling Liverpool and stereotyping Scousers’, Cities, 25(6), pp. 355–369. Bryman, A. (2012) Social research methods. 4th edn. New York: Oxford University Press. Clarke, N. (2009). Britain’s worst neighbourhoods. [online] AskMen. Available at: https://uk.askmen.com/entertainment/special_feature_250/273b_top-10-dodgy-british-neighbourhoods.html [Accessed 24 Jan. 2018]. Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: SAGE. Wildman, C. (2012) ‘Urban transformation in Liverpool and Manchester, 1918–1939’, The Historical Journal, 55(01), pp. 119–143. Biography Alice Butler is a PhD student at the University of Leeds, based in the School of Geography. She researches the production of territorial stigmatization and denigration, particularly in relation to the city of Liverpool. In addition, she is involved in research about the use and effects of the discourse of denigration on social media. Alice has a BA in French and Middle Eastern Studies and a MA in Politics.

0 Comments

|

AuthorMembers of the Documents Research Network Archives

June 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed