Time to Return to the Past: Reporting on the BSA-British Library Sociology in the Archives Workshop9/7/2018 George Jennings, Cardiff Metropolitan University The array of information leaflets available at the British Library Image courtesy of George Jennings Archives are often overlooked in research methods courses and textbooks, as well as by experienced researchers in many social sciences. Yet this is about to change. I was honoured to be invited to the British Library to take part in an exciting one-day event: The “Sociology in the Archives” workshop jointly run by the British Library (fondly known among them as “the BL”) and the British Sociological Association (BSA). Andy Rackley – who contributed an excellent blog for the DRN on his background with archives – kindly invited me to represent our network. With a programme packed full of expert scholars and collection specialists, I was very pleased to be one of the lucky 39 attendees, hailing from local institutions and across the country – even as far as Edinburgh. Following introductions by directors of research and executives form both institutions, Andy offered a useful portrait of archival research and some of the core textbooks that we, as researchers, can engage with (such as Moore, Salter, Stanley and Tamboukou, 2016). His project within the BSA helped develop this event, which aimed to highlight the role of archival research in the methodological canon for sociologists.

The BSA is taking a stronger, almost fervent interest in archival research. They are not only supporting primary data collection seen in ethnographic work, but have envisaged an “Archives Prize” for the best piece of archival research at the BSA Annual Conference. As the sociological panel of Liz Stanley, Aaron Winter, Nirmal Puwar and Kahryn Hughes demonstrated, archives are not just the preserve of historians or librarians, but can be put into action by social scientists examining the links between the past and the present. Their eclectic interests were brought together around the themes of race and ethnicity as well as equality and diversity – two current priorities for the BSA. Edinburgh professor Liz Stanley shared her work on the construction of “race” in colonialist South Africa, while the University of East London’s Aaron Winter examined the alarming racist discourse and ideology of far-right groups in the United States. Continuing in this vein, Goldsmiths professor Nirmal Puwar shared excerpts of an innovative postcolonialist film about Indian soldiers serving during the Second World War. Following that, Kahryn Hughes of the University of Lincoln (speaking also on behalf of Anna Tarrant of Leeds) provided a methodological overview of their thorough approach to using archives as methods. Following this eclectic plenary from the academics, the lunch break and buffet allowed delegates to network and connect with each other, and I am grateful to be in contact with numerous scholars with very interesting portfolios of work. Throughout these breaks, I also perused the numerous leaflets that showed just how much the BL has to offer students, lecturers and researchers: From specialist collections of regions such as Latin America and Asia (with specialists in numerous countries) to experts in particular methods, such as oral history. Allan Sudlow, the Head of Research Engagement at the BL, provided a useful introduction to this, with his overview of what the British Library can do (and, very honestly, cannot) – addressing the what, why, how and when questions we researchers might pose. The BL has some impressive presenters and scholarly experts, and this was expressed by the talks from Mary Stewart (a proponent of oral history), Debbie Cox (a curator of British published collections) and D-M Withers, an early career research fellow interested in gender. Chatting to some of them afterwards, I was also impressed by how the methods of using archives allowed for the BL team to rotate around departments and cultivate new knowledge and skills – something that an ethnographer might be familiar with. The day ended with a lively roundtable discussion on “Archives in the sociological research process”, where Andy invited me to provide a voice for the DRN. Eyes pricked up and keen nods emerged when I told them about our supportive space for anyone using documents as data across the disciplines. The delegates also seemed very pleased with the prospect of future specialist events on archives, and I have since been in touch with Judith Mudd, the Chief Executive of the BSA, to keep the DRN involved in these meetings and developments. Moreover, there was even talk of a pioneering methods textbook that could include a chapter on archival research – so lacking across the disciplines. We were so enthused that many participants stayed on speaking at length about their work over wine and refreshments, and some took advantage of the setting to visit exhibitions, such as one on Karl Marx that very evening. So, after this exciting day out, I can safely say that archives are very much alive and kicking, and the time is ripe to make the most of them. It is time to return to the past. Reference Moore, N., Salter, A., Stanley, L. and Tamboukou, M. (2016). The archive project. Archival research in the social sciences. London: Routledge. Biography George Jennings is a lecturer in sport sociology / physical culture at Cardiff Metropolitan University, where he teaches modules relating to contemporary issues in sport, social theory and qualitative methods. A keen methodologist, George has used autophenomenography, ethnography, life history and narrative approaches alongside documental analysis to examine martial arts cultures, pedagogies and philosophies. George is the co-founder of Documents Research Network (DRN) and is the academic consultant for DojoTV.

1 Comment

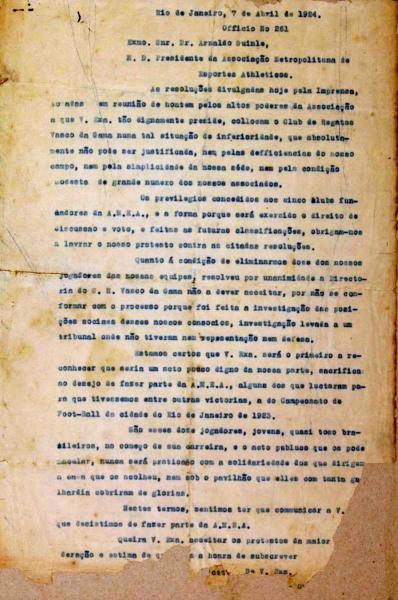

Igor Serrano, Sports Lawyer, Brazilian Anti-Doping Court The Vasco team in 1923  As a sports lawyer I often work with cases of football players involved in episodes of racism, whether it be with opponents or supporters. If it were not for the document known as The Historical Answer, the number of cases today would certainly be much higher or we might even be facing the same scenario of that time: a League practically played and controlled by white and rich athletes. Below I outline some of the important findings within The Historical Answer.For a long time, the international community mistakenly saw Brazil as a model for racial democracy. In 1951, influenced by Gilberto Freyre, UNESCO commissioned several specialists to study the supposed model of Brazilian success. One of them, Florestan Fernandes, to UNESCO’s surprise, presented the opposite conclusion: instead of democracy, there was discrimination. In the place of harmony, prejudice. According to Florestan Fernandes, there was a particular form of Brazilian racism: "a prejudice to have prejudice" - the tendency to maintain discrimination.. It was a shameful expression practiced within intimate fora. According to Fernandes, the abolition of slavery in Brazil blocked the freed people the opportunity to act civilly and politically in the struggle for their rights, which consequently overlooked a modification of the traditional pattern of racial accommodation. In Richard Giulianotti's teachings, "Football is certainly shaped by and within a more general society, but it produces a universe of power relations, meanings, discourses, and aesthetic styles." And it was a football club Club de Regatas Vasco da Gama founded in 1898, in Rio de Janeiro, by 62 Portuguese and Brazilian men, that was responsible for fighting against racism and to give a contribution to reduce the prejudice against black athletes. At the dawn of the 19th century, it was very common for rich families in Brazil to send their sons to study in Europe. This exchange allowed rich young Brazilians to have contact with football and made them return to Brazil in a decisive way to develop the sport, even if, initially, they used football to discriminate against the popular strata. The first recorded match happened in 1895, in São Paulo, just three years before the foundation of Club de Regatas Vasco da Gama. Racism an undeniable reality in Brazilian society and football with significant social effects: just three decades after the abolition of slavery, blacks were free but without any education to enable them to survive in a new reality. Most of them were forced to work with newly arrived immigrants who did not suffer the same consequences of racism and better understood capitalism. The disadvantage of black people in the labor market was evident: most of them ended up being subjected to inglorious tasks to gain modest payments. However, on the pitch, it disappeared: the quality of black players was visible, and began to take the attention of the rich teams in Rio. In addition to four black players, Vasco had in its team four semi-literates and was a club of the Portuguese colony, suffering prejudice of the Rio de Janeiro rivals. But the team had an important ally: the large number of poor Portuguese and Brazilians fans who identified themselves with the club. The incredible number of fans enabled Vasco to rent the stadium of Fluminense to play some home matches. Black Brazilians and Portuguese immigrants found in Vasco, the possibility to stand out in a country marked by the social inequality. Football was the opportunity they needed and Vasco offered a welcome to exalt them with their achievements on the football pitches. The admiration for Vasco only increased in the fans when the team continued playing good football and became champions in 1923. Notable players in this victorious campaign were: Nelson (cab driver), Leitão (semi-literate, factory worker) and Mingote (wall painter); Nicolino (black, former Andaraí player), Bolão (black, truck driver) and Arthur (referee in Rio suburbs); Paschoal (employee in furniture factory), Torterolli (factory worker), Arlindo (first player of a high social class to play for Vasco; former Botafogo player), Cecy (wall painter) and Negrito (discovered in a local team). Unhappy with Vasco’s title, the inclusion practices defended by the club and the threat to the status quo, Botafogo, Flamengo, Fluminense and América came together to change the game. They decided to create a new league, parallel to the MLGS and that, would involve only Rio’s rich teams. In this way, the new league, Metropolitan Association of Athletic Sports (MAAS), was created on March 1st, 1924. Vasco, excluded from the new league, had to be approved by MAAS members in order to participate. In its statute, MAAS determined, among other predictions, that clubs interested in becoming affiliated should indicate all possible data on their athletes, including their residence and profession, with the indication of a boss for evidence. Even with these requirements, which made Vasco's participation in MAAS difficult, the club filed its application for membership. With the request for affiliation received, MAAS decided to tighten conditions for Vasco: The League determined the exclusion of 12 players because they were semi-literate, black or of humble origin. Vasco's managers, revolted by the situation, opted for the resignation of the application for MAAS League membership. This was declared in a letter signed by the President José Augusto Prestes (of April 7th, 1924), which became known as The Historical Answer. The Historical Answer Without the MAAS championship to play, Vasco kept in action against other teams that also did not take part in the competition. Their fans remained faithful and attended in large numbers to the team's matches, and this began to reflect financially on Rio’s rich clubs. Vasco occasionally rented the stadia of clubs like Flamengo, Fluminense and Botafogo for its well-attended matches. After not joining MAAS, the Club ceased this. The multitude of Vasco fans were normally guarantee of good box office revenues in the matches against those teams. Although they did not want Vasco near them, the elitist teams soon realized that they needed it for financial security. In 1925, the MAAS League leaders changed their minds and recognized Vasco as being able to compete in their championship. Vasco demanded guarantees: to have the same rights as the other clubs. Its players were accepted without discrimination, which was a great achievement in an attempt to promote social justice in football. For what it was, the Club de Regatas Vasco da Gama made a great contribution to the history of world football and to the ongoing struggle for a more just and democratic Brazilian society without racial or social discrimination. BIBLIOGRAPHY ASSAF, Roberto and MARTINS, Clovis. História dos Campeonatos Cariocas de Futebol, 1906/2010. Rio de Janeiro: Maquinária, 2010. FERNANDES, Florestan. O negro no mundo dos brancos. Apresentação de Lilia Moritz Schwarcz. 2ª ed. rev. São Paulo: Global, 2007. GIULIANOTTI, Richard. Sociologia do futebol: dimensões históricas e socioculturais do esporte das multidões. Tradução de Wanda Nogueira Caldeira Brant e Marcelo Oliveira Nunes. São Paulo: Nova Alexandria, 2010. MALAIA SANTOS, João Manuel Casquinha. Revolução Vascaína: a profissionalização do futebol e inserção sócio-econômica de negros e portugueses na cidade do Rio de Janeiro (1915-1934). Universidade de São Paulo, 2010. p. 343. Available in: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/8/8137/tde-26102010-115906/pt-br.php. Acess in June/2018. SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz. Nem preto nem branco, muito pelo contrário: cor e raça na sociabilidade brasileira. São Paulo: Claro Enigma, 2012. VEIGA, Maurício de Figueiredo Côrrea da. Temas atuais do Direito Desportivo. São Paulo: LTR, 2015. VENÂNCIO, Pedro. Nasce o Gigante da Colina. Rio de Janeiro: Maquinária, 2014. Websites: http://www.vasco.com.br/site/noticia/detalhe/1483393-anos-da-resposta-historica-1924-2017. Acess in June/2018. Author biography Igor Serrano is a Sports Lawyer and a Public Defender in the Brazilian Antidoping Sports Court. He researches the racism in Brazilian football and is also editor and creator of the football books label Drible de Letra (Multifoco Publishing). |

AuthorMembers of the Documents Research Network Archives

June 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed