|

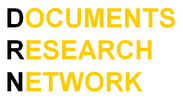

Mark Langweiler, London South Bank University English language edition of the Gold Book Image courtesy of Mark Langweiler Within the martial arts community and, more specifically, the tai chi family arts, written documentation is rare. Over the years, there had been rumours of such writings within the Wu family yet little evidence was forthcoming especially in the West. While portions of Wu Kung Cho’s text were known in China in the early 20th century, it wasn’t until the end of the last century that the full text became available in Chinese and not until 2006 that an English language version approved by the Wu family became available. The publication of the ‘Gold Book’ was a significant event given the lack of accurate martial arts publications at the time. This blog offers an exploration of this important methodological text and the issues surrounding the transmission of Wu family tai chi knowledge to the wider world. Wu Style Tai Chi Chuan - The Origins Within the study of the martial arts, there are two strands: the external or hard styles, which includes martials arts such as kung fu or karate, and the internal or soft styles, of which tai chi chuan is the best known. The basic premise of tai chi chuan is that softness used appropriately can overcome force. The practice develops this sense of soft power, relaxation and the development of qi or internal energy. The origins of tai chi chuan remain uncertain with no direct documentation of its beginnings, there is, however, some historical evidence from the Ming Dynasty[1] concerning a Taoist monk, Chang San Feng, being invited to teach at the Imperial court. If so, tai chi chuan dates back 600 years. Wu style tai chi chuan traces its lineage to the Qing Dynasty[2] during the reign of the Emperor Tongzhi (1862-1874)[3]. Wu Chuan Yau (1834-1902), a captain in the Imperial court, studied tai chi chuan with masters Yang Lu Chan (1799-1872), founder of Yang style, and his son, Yang Ban Hou (1837-1890). For political reasons, it was thought best that Wu Chuan Yau be made a disciple of Yang Ban Hou rather than his father. Wu Chuan Yau taught his son, Wu Chien Chuan, who altered the tai chi form making the movements smaller and developed many new martial applications. Wu Chien Chuan, along with several other martial artists, including Yang Cheng Fu (grandson of Yang style founder Yang Lu Chan) opened the Beijing School of Physical Education. Among the first graduates where Wu Kung Yi (1900-1970) and Wu Kung Cho (1903-1983). Wu Kung Cho was considered to be a master of all aspects of the Wu style with special emphasis on qigong or the practice of internal energy. Five generations of the Wu family have handed down a training manual for Wu style tai chi chuan. The ‘Gold Book’, (so named due to the colour of the 1980 Chinese edition) was first compiled in 1935 by Wu King Cho, the grandson of Wu style founder Wu Chuan Yau. Wu Kung Cho had originally planned on writing a two-part thesis but due to family obligations and personal problems, this was limited to the first. Tragically, he was imprisoned by the Chinese communists from 1950 until 1979 and was only released following the fall of the ‘Gang of Four’[4]. He spent his final years in Hong Kong with his family. The Gold Book original Chinese edition

Image courtesy of Mark Langweiler The 1935 edition of the text is composed of 15 short chapters detailing the complete aspects of the Wu family tai chi chuan style. While teaching at the Hunan Martial Arts Training Centre, Wu Kung Cho came to the realisation that relying solely on word of mouth would lead to misunderstandings and the eventual watering down of the style. To prevent this, he wrote the text detailing the Wu style. There are several appendices of tai chi verse written by unknown practitioners and a prologue by Xiang Kairen, a well-known Chinese novelist of the time. The text includes a discourse on the philosophy underlying tai chi practice, sections on the tai chi form, push hands, the eight methods, and winding silk and neutralisation, an action for which Wu style is particularly known. Wu Kung Cho had intended to complete the text with a second part based on the teachings of Yang Ban Hou, ‘The Methodology of Tai Chi Chuan’. This had to wait until the 1980 edition. Following his release from the concentration camp, Wu Kung Cho dedicated himself to completing the ‘Gold Book’. This time, he was able to include all of the material he had planned for the earlier edition. The Yang Ban Hou manuscript is composed of 40 brief paragraphs outlining the practices passed on to the Wu family, its relationship to Taoist philosophy and applications for self-defence. Additionally, a postscript written by Jin Yong, author of ‘Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon,’ has been added. The current English language translation was self-published by the Wu Style Federation in 2006. It includes all of the contents of the 1980 Chinese edition as well as series of photos of Wu Chien Chuan and Wu Kung Yi doing the Wu family form. Neither set is a complete version but both present the essence of the form. There is also a copy of the original 1935 publication. The book ends with brief biographies of the Wu family. In discussions with Doug Woolidge, the translator, he commented that each sentence, often each word had to be reviewed and discussed with the advisory board since Chinese characters can have multiple, sometimes diverging meanings. This can lead to a great deal of confusion as had been seen in other translations. Unfortunately, the 2006 English language edition is now out of print, though the occasional volume may still be found. The 1980 Chinese Version can be found on the Wu style tai chi chuan web page. A search is currently on for a new publisher who can take this treasure of the Wu family into the public sphere. Maintaining the availability of texts such as the ‘Gold Book’ is important for several reasons. Certainly the historical context. In the case of the ‘Gold Book’, the Wu family were fortunate that there existed several copies outside of mainland China that Wu Kung Cho could use to rebuild his work. But there are also issues of pedagogy, how the arts were taught and why. Wu Style was lucky, but the political atmosphere during the early communist period led to the disappearance of entire martial arts lineages. Having written documentation could have prevented that from occurring. Reference The Gold Book Editors - Rosalind Gill and Peter Harries-Jones Translator - Doug Woolidge Publisher - Jonathen Krehm on behalf of the Wu Style Tai Chi Federation, 2006 Includes the classic text- Explanations of Tai Chi Methodology Written by Yang Ban Hou Notes

1 Comment

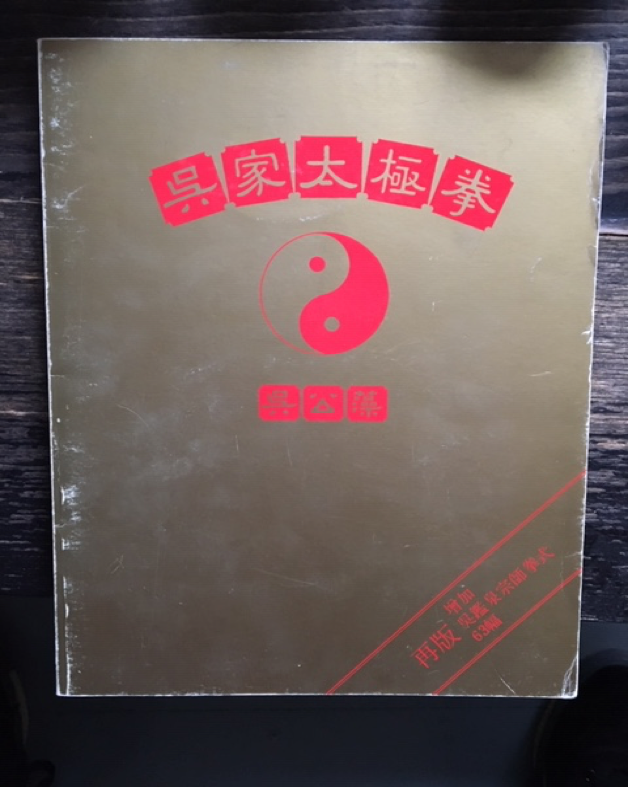

Louise Hoyle, University of Stirling [Article: Hoyle, L. P., Smith, E., Mahoney, C., & Kyle, R. G. (2018). Media Depictions of “Unacceptable” Workplace Violence Toward Nurses. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154418802488.] I have an interest in how the media reports issues that focus on healthcare in the UK. I am always keen to understand particular issues are framed by the media and how this can influence the perceptions of the general public. For example, I worked with Dr Aimee Grant to look at print media representations of UK Accident and Emergency Treatment Targets (Grant & Hoyle 2017). Also, in previous work, I looked at how nursing staff viewed the impact of mass media has on service users and what this means for interactions between nurses and service users (Hoyle, Kyle & Mahoney 2017). Media framing exerts a clear influencing on the public’s perceptions of healthcare professionals and services and so healthcare professionals need to understand the messages that the general public receive and to consider how health stories are reported. Following this research I therefore thought it would be interesting to see how the Scottish Media reports cases of violence and aggression towards nursing staff in Scotland. Being a registered nurse and having worked within acute hospital settings, my research as an academic focuses on violence, aggression, bullying and harassment within nursing. So, we decided to undertake a thematic analysis of newspaper articles reporting incidents of violence and aggression within Scotland between 2006- 2016 (a ten-year period). The articles were identified by searching NEXIS® and BBC News online. Much of what was done is similar to the way the Grant & Hoyle (2017) paper was carried out (discussed in Grant, 2018). However, within this blog I want to talk about two key elements of the research reported in Hoyle et al, (2018), first is the use of the PRISMA checklist (Moher et al. 2009) within the identification of the papers and secondly, in using the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines (O’Brien et al. 2014) to aid in the write up of the project. The Use of PRISMA PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (Moher et al. 2009), was adapted for the purposes of undertaking the search for articles on violence and aggression within the media in Scotland. PRISMA was originally developed as a basis to aid the reporting of systematic reviews and other types of research. There is a 27-item checklist and a flow diagram for displaying the search and selection strategy of papers (http://www.prisma-statement.org/). In the article we were not undertaking a systematic review or meta-analysis, but it was felt that some of the principles from PRISMA help with the reporting of the newspaper articles and display of the search. What was of most interest is the flow diagram that is provided by PRISMA (Moher et al. 2009). It is this flow diagram that can enable researchers to record their search in a clear way. It was this that we used within our own study looking at violence and aggression reporting in print media. This allowed us to display our newspaper search strategy in a clear way which makes it accessible for readers (Figure 1). We then used the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines (O’Brien et al. 2014) to report the qualitative results from this study. This provides a checklist to ensure that there was transparency when reporting study findings. It is considered good practice to use such guidelines when writing up studies, and often this is now a requirement for publishing in journals in the health and medical sciences[1]. The SRQR asks the authors to ensure that certain elements are included within the write up of the study; this is where these elements were reported in our article. Adhering to such guidelines is good practice when writing up a study and ensures that you are reporting the all elements that are required in order for someone to make a judgement about the quality of the research.

Readers interested in the study and the SRQR procedures are most welcome to contact me by email: [email protected] References: Grant, A. (2019). Doing excellent social research with documents. London: Routledge. Grant, A., & Hoyle, L. (2017). Print media representations of UK Accident and Emergency treatment targets: Winter 2014-2015. Journal of Clinical Nursing2 6(23-24), 4425-4435 DOI:10.1111/jocn.13772 Hoyle, L. P., Kyle, R., & Mahoney, C. (2017). Nurses’ views on the impact of mass media on the public perception of nursing and nurse–service user interactions. Journal of Research in Nursing, 22(8), 586-596 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987117736363 Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 339, b2535. DOI: doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535 O'Brien B. C., Harris I. B., Beckman T. J., Reed D. A., Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245-1251. [1] The EQUATOR Network (https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/) provides an overview of reporting guidelines for the main study types. Biography Louise Hoyle is a registered adult nurse (RN) and a lecturer in nursing at The University of Stirling. Louise has research interests in the fields of: workplace violence and aggression, the working conditions of nurses, the health & wellbeing of nursing workforce, and health reporting in the media. Louise has a PhD in Sociology & Social Policy and MScs’ in Criminology and Applied Social Research. Time to Return to the Past: Reporting on the BSA-British Library Sociology in the Archives Workshop9/7/2018 George Jennings, Cardiff Metropolitan University The array of information leaflets available at the British Library Image courtesy of George Jennings Archives are often overlooked in research methods courses and textbooks, as well as by experienced researchers in many social sciences. Yet this is about to change. I was honoured to be invited to the British Library to take part in an exciting one-day event: The “Sociology in the Archives” workshop jointly run by the British Library (fondly known among them as “the BL”) and the British Sociological Association (BSA). Andy Rackley – who contributed an excellent blog for the DRN on his background with archives – kindly invited me to represent our network. With a programme packed full of expert scholars and collection specialists, I was very pleased to be one of the lucky 39 attendees, hailing from local institutions and across the country – even as far as Edinburgh. Following introductions by directors of research and executives form both institutions, Andy offered a useful portrait of archival research and some of the core textbooks that we, as researchers, can engage with (such as Moore, Salter, Stanley and Tamboukou, 2016). His project within the BSA helped develop this event, which aimed to highlight the role of archival research in the methodological canon for sociologists.

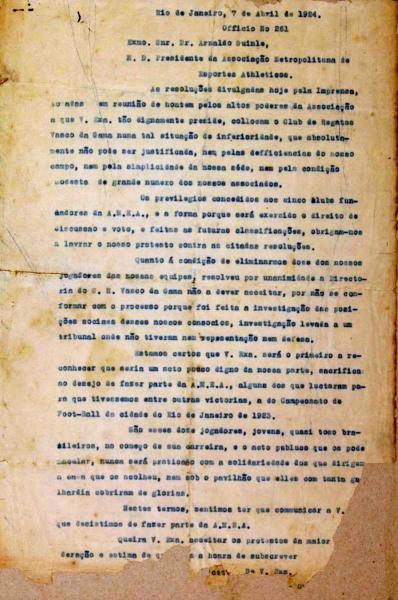

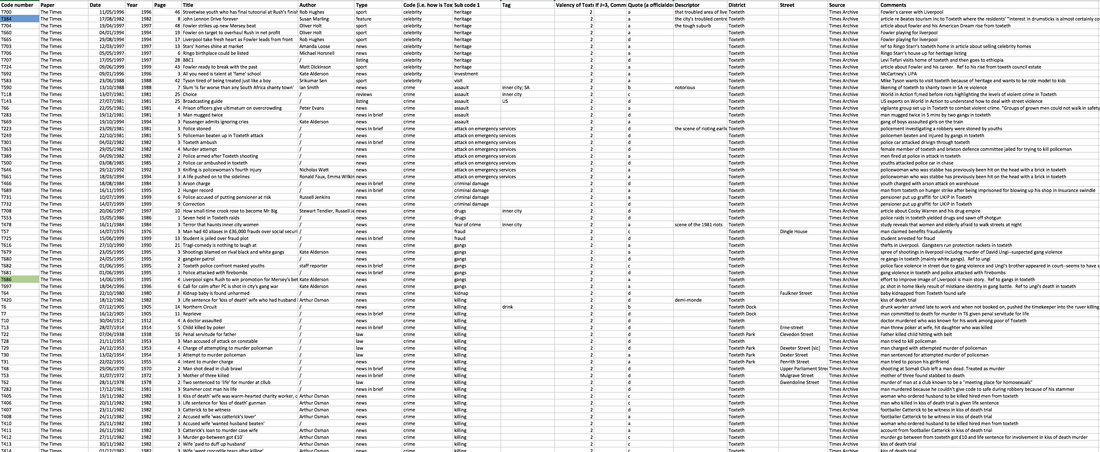

The BSA is taking a stronger, almost fervent interest in archival research. They are not only supporting primary data collection seen in ethnographic work, but have envisaged an “Archives Prize” for the best piece of archival research at the BSA Annual Conference. As the sociological panel of Liz Stanley, Aaron Winter, Nirmal Puwar and Kahryn Hughes demonstrated, archives are not just the preserve of historians or librarians, but can be put into action by social scientists examining the links between the past and the present. Their eclectic interests were brought together around the themes of race and ethnicity as well as equality and diversity – two current priorities for the BSA. Edinburgh professor Liz Stanley shared her work on the construction of “race” in colonialist South Africa, while the University of East London’s Aaron Winter examined the alarming racist discourse and ideology of far-right groups in the United States. Continuing in this vein, Goldsmiths professor Nirmal Puwar shared excerpts of an innovative postcolonialist film about Indian soldiers serving during the Second World War. Following that, Kahryn Hughes of the University of Lincoln (speaking also on behalf of Anna Tarrant of Leeds) provided a methodological overview of their thorough approach to using archives as methods. Following this eclectic plenary from the academics, the lunch break and buffet allowed delegates to network and connect with each other, and I am grateful to be in contact with numerous scholars with very interesting portfolios of work. Throughout these breaks, I also perused the numerous leaflets that showed just how much the BL has to offer students, lecturers and researchers: From specialist collections of regions such as Latin America and Asia (with specialists in numerous countries) to experts in particular methods, such as oral history. Allan Sudlow, the Head of Research Engagement at the BL, provided a useful introduction to this, with his overview of what the British Library can do (and, very honestly, cannot) – addressing the what, why, how and when questions we researchers might pose. The BL has some impressive presenters and scholarly experts, and this was expressed by the talks from Mary Stewart (a proponent of oral history), Debbie Cox (a curator of British published collections) and D-M Withers, an early career research fellow interested in gender. Chatting to some of them afterwards, I was also impressed by how the methods of using archives allowed for the BL team to rotate around departments and cultivate new knowledge and skills – something that an ethnographer might be familiar with. The day ended with a lively roundtable discussion on “Archives in the sociological research process”, where Andy invited me to provide a voice for the DRN. Eyes pricked up and keen nods emerged when I told them about our supportive space for anyone using documents as data across the disciplines. The delegates also seemed very pleased with the prospect of future specialist events on archives, and I have since been in touch with Judith Mudd, the Chief Executive of the BSA, to keep the DRN involved in these meetings and developments. Moreover, there was even talk of a pioneering methods textbook that could include a chapter on archival research – so lacking across the disciplines. We were so enthused that many participants stayed on speaking at length about their work over wine and refreshments, and some took advantage of the setting to visit exhibitions, such as one on Karl Marx that very evening. So, after this exciting day out, I can safely say that archives are very much alive and kicking, and the time is ripe to make the most of them. It is time to return to the past. Reference Moore, N., Salter, A., Stanley, L. and Tamboukou, M. (2016). The archive project. Archival research in the social sciences. London: Routledge. Biography George Jennings is a lecturer in sport sociology / physical culture at Cardiff Metropolitan University, where he teaches modules relating to contemporary issues in sport, social theory and qualitative methods. A keen methodologist, George has used autophenomenography, ethnography, life history and narrative approaches alongside documental analysis to examine martial arts cultures, pedagogies and philosophies. George is the co-founder of Documents Research Network (DRN) and is the academic consultant for DojoTV. Igor Serrano, Sports Lawyer, Brazilian Anti-Doping Court The Vasco team in 1923  As a sports lawyer I often work with cases of football players involved in episodes of racism, whether it be with opponents or supporters. If it were not for the document known as The Historical Answer, the number of cases today would certainly be much higher or we might even be facing the same scenario of that time: a League practically played and controlled by white and rich athletes. Below I outline some of the important findings within The Historical Answer.For a long time, the international community mistakenly saw Brazil as a model for racial democracy. In 1951, influenced by Gilberto Freyre, UNESCO commissioned several specialists to study the supposed model of Brazilian success. One of them, Florestan Fernandes, to UNESCO’s surprise, presented the opposite conclusion: instead of democracy, there was discrimination. In the place of harmony, prejudice. According to Florestan Fernandes, there was a particular form of Brazilian racism: "a prejudice to have prejudice" - the tendency to maintain discrimination.. It was a shameful expression practiced within intimate fora. According to Fernandes, the abolition of slavery in Brazil blocked the freed people the opportunity to act civilly and politically in the struggle for their rights, which consequently overlooked a modification of the traditional pattern of racial accommodation. In Richard Giulianotti's teachings, "Football is certainly shaped by and within a more general society, but it produces a universe of power relations, meanings, discourses, and aesthetic styles." And it was a football club Club de Regatas Vasco da Gama founded in 1898, in Rio de Janeiro, by 62 Portuguese and Brazilian men, that was responsible for fighting against racism and to give a contribution to reduce the prejudice against black athletes. At the dawn of the 19th century, it was very common for rich families in Brazil to send their sons to study in Europe. This exchange allowed rich young Brazilians to have contact with football and made them return to Brazil in a decisive way to develop the sport, even if, initially, they used football to discriminate against the popular strata. The first recorded match happened in 1895, in São Paulo, just three years before the foundation of Club de Regatas Vasco da Gama. Racism an undeniable reality in Brazilian society and football with significant social effects: just three decades after the abolition of slavery, blacks were free but without any education to enable them to survive in a new reality. Most of them were forced to work with newly arrived immigrants who did not suffer the same consequences of racism and better understood capitalism. The disadvantage of black people in the labor market was evident: most of them ended up being subjected to inglorious tasks to gain modest payments. However, on the pitch, it disappeared: the quality of black players was visible, and began to take the attention of the rich teams in Rio. In addition to four black players, Vasco had in its team four semi-literates and was a club of the Portuguese colony, suffering prejudice of the Rio de Janeiro rivals. But the team had an important ally: the large number of poor Portuguese and Brazilians fans who identified themselves with the club. The incredible number of fans enabled Vasco to rent the stadium of Fluminense to play some home matches. Black Brazilians and Portuguese immigrants found in Vasco, the possibility to stand out in a country marked by the social inequality. Football was the opportunity they needed and Vasco offered a welcome to exalt them with their achievements on the football pitches. The admiration for Vasco only increased in the fans when the team continued playing good football and became champions in 1923. Notable players in this victorious campaign were: Nelson (cab driver), Leitão (semi-literate, factory worker) and Mingote (wall painter); Nicolino (black, former Andaraí player), Bolão (black, truck driver) and Arthur (referee in Rio suburbs); Paschoal (employee in furniture factory), Torterolli (factory worker), Arlindo (first player of a high social class to play for Vasco; former Botafogo player), Cecy (wall painter) and Negrito (discovered in a local team). Unhappy with Vasco’s title, the inclusion practices defended by the club and the threat to the status quo, Botafogo, Flamengo, Fluminense and América came together to change the game. They decided to create a new league, parallel to the MLGS and that, would involve only Rio’s rich teams. In this way, the new league, Metropolitan Association of Athletic Sports (MAAS), was created on March 1st, 1924. Vasco, excluded from the new league, had to be approved by MAAS members in order to participate. In its statute, MAAS determined, among other predictions, that clubs interested in becoming affiliated should indicate all possible data on their athletes, including their residence and profession, with the indication of a boss for evidence. Even with these requirements, which made Vasco's participation in MAAS difficult, the club filed its application for membership. With the request for affiliation received, MAAS decided to tighten conditions for Vasco: The League determined the exclusion of 12 players because they were semi-literate, black or of humble origin. Vasco's managers, revolted by the situation, opted for the resignation of the application for MAAS League membership. This was declared in a letter signed by the President José Augusto Prestes (of April 7th, 1924), which became known as The Historical Answer. The Historical Answer Without the MAAS championship to play, Vasco kept in action against other teams that also did not take part in the competition. Their fans remained faithful and attended in large numbers to the team's matches, and this began to reflect financially on Rio’s rich clubs. Vasco occasionally rented the stadia of clubs like Flamengo, Fluminense and Botafogo for its well-attended matches. After not joining MAAS, the Club ceased this. The multitude of Vasco fans were normally guarantee of good box office revenues in the matches against those teams. Although they did not want Vasco near them, the elitist teams soon realized that they needed it for financial security. In 1925, the MAAS League leaders changed their minds and recognized Vasco as being able to compete in their championship. Vasco demanded guarantees: to have the same rights as the other clubs. Its players were accepted without discrimination, which was a great achievement in an attempt to promote social justice in football. For what it was, the Club de Regatas Vasco da Gama made a great contribution to the history of world football and to the ongoing struggle for a more just and democratic Brazilian society without racial or social discrimination. BIBLIOGRAPHY ASSAF, Roberto and MARTINS, Clovis. História dos Campeonatos Cariocas de Futebol, 1906/2010. Rio de Janeiro: Maquinária, 2010. FERNANDES, Florestan. O negro no mundo dos brancos. Apresentação de Lilia Moritz Schwarcz. 2ª ed. rev. São Paulo: Global, 2007. GIULIANOTTI, Richard. Sociologia do futebol: dimensões históricas e socioculturais do esporte das multidões. Tradução de Wanda Nogueira Caldeira Brant e Marcelo Oliveira Nunes. São Paulo: Nova Alexandria, 2010. MALAIA SANTOS, João Manuel Casquinha. Revolução Vascaína: a profissionalização do futebol e inserção sócio-econômica de negros e portugueses na cidade do Rio de Janeiro (1915-1934). Universidade de São Paulo, 2010. p. 343. Available in: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/8/8137/tde-26102010-115906/pt-br.php. Acess in June/2018. SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz. Nem preto nem branco, muito pelo contrário: cor e raça na sociabilidade brasileira. São Paulo: Claro Enigma, 2012. VEIGA, Maurício de Figueiredo Côrrea da. Temas atuais do Direito Desportivo. São Paulo: LTR, 2015. VENÂNCIO, Pedro. Nasce o Gigante da Colina. Rio de Janeiro: Maquinária, 2014. Websites: http://www.vasco.com.br/site/noticia/detalhe/1483393-anos-da-resposta-historica-1924-2017. Acess in June/2018. Author biography Igor Serrano is a Sports Lawyer and a Public Defender in the Brazilian Antidoping Sports Court. He researches the racism in Brazilian football and is also editor and creator of the football books label Drible de Letra (Multifoco Publishing). Alice Butler, School of Geography,University of Leeds Readers of this blog are familiar with a variety of practices used to analyse documents. This piece serves as a reflection on what is often seen as a confusing step in planning a textual analysis: creating a coding structure. I am a Human Geographer based at the University of Leeds where I am researching the historical formation of territorial stigma in relation to the district of Toxteth in Liverpool. Toxteth and Liverpool have a poor reputation (Boland, 2008) and Scousers—residents of Liverpool—are stigmatized particularly in the media where they are caricatured as being work-shy scroungers, morally degenerate and deviant (Boland, 2008). Liverpool is “synonymous with vandalism, with high crime, with social deprivation in the form of bad housing, with obsolete schools, polluted air and a polluted river, with chronic unemployment, run-down dock systems and large areas of dereliction” (Marriner, 1982 in Wildman, 2012: 119). Toxteth, a district to the south of the city centre, is particularly stung by a poor reputation with popular magazines and websites warning the public that Toxteth and its residents are dangerous; a popular men’s online magazine reporting that “shootings are a regular thing here, and pedestrians can almost certainly expect to run into trouble” (Clarke, 2009). I want to know how this pernicious reputation came to have such a grip on Toxteth. For this, I have turned to online newspaper archives and I have spent the last year scouring the Times, the Guardian, the Mirror, the Financial Times, and the Express archives from for the 20th century. I have completed a mixed quantitative-qualitative content analysis (borrowing heavily from the Critical Discourse Analysis tradition) of 1,950 newspaper articles that mention the term ‘Toxteth’. Putting together a coding structure can often be a daunting prospect and it is to that which I turn in the rest of this short piece. My coding schedule—the database into which the data and codes are entered—came about after a period of reflection: what did I want to find out through analysis? I wanted to know how the press stigmatized Toxteth in their coverage during the 20th century and, for this, I needed to note the appearance of certain words or phrases. I needed columns to hold the date of publication so that I could trace the use of these words or phrases over time. I needed to know who was quoted in articles and who was denied a voice, so I added columns for quotation source. Further, I wanted to mark whether articles portrayed Toxteth and events in Toxteth in a positive, negative or neutral manner, so I added a column for valency to reflect this. Finally, I needed columns to code for how Toxteth was mentioned in each article. This was the trickiest part of developing the coding structure as I had to develop codes and sub-codes that would reflect the content of the texts. A code is “a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing, and/or evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data” (Saldaña, 2009: 3). It can be thought of as capturing the essence of data in much the same way as a title captures the essence of a book, film or poem (Saldaña, 2009: 3). In a quantitative study, codes are generally predetermined, separate from the text under analysis. In a qualitative study, the codes are “refined” during the coding and analysis process (Bryman, 2012: 559). For my work, I used a pilot study of regional newspapers that I didn’t include in my final analysis all available through the British Newspaper Archive, which helped me to determine some codes to be used in the main study, but I followed a qualitative coding approach that allowed me to generate new codes during the coding process. The codes, then, are generated based on what the text contains. For my research, I asked the question: in what capacity is Toxteth mentioned in this text? I allowed myself to develop as many codes as necessary in the initial first cycle of analysis (Saldaña, 2009: 3) and these codes covered everything from car accidents, race relations, and promiscuity, to community relations, deprivation, and drugs raids (see image below). It was at the second cycle of analysis that I condensed these codes and, for example, re-coded “burglary”, “robbery and “theft” all as “theft”. I also went back through the data and sorted the individual codes into “families” or categories (Saldaña, 2009: 8) that make the data easier to manage. Categories include umbrella terms such as “crime”, “riots”, and “politics” and the revised codes form the sub-codes within each category. Coding in this fashion can be a time-consuming and laborious process; this project took many months to complete. It is worth putting the time in to reflect on what you want the analysis of the text to reveal, and to spend some time conducting a trial or pilot study to test out an initial coding structure even if you intend to let codes generate during the analysis. However, the results are detailed and, if planned correctly, can provide a comprehensive way to understand texts. References Boland, P. (2008) ‘The construction of images of people and place: Labelling Liverpool and stereotyping Scousers’, Cities, 25(6), pp. 355–369. Bryman, A. (2012) Social research methods. 4th edn. New York: Oxford University Press. Clarke, N. (2009). Britain’s worst neighbourhoods. [online] AskMen. Available at: https://uk.askmen.com/entertainment/special_feature_250/273b_top-10-dodgy-british-neighbourhoods.html [Accessed 24 Jan. 2018]. Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: SAGE. Wildman, C. (2012) ‘Urban transformation in Liverpool and Manchester, 1918–1939’, The Historical Journal, 55(01), pp. 119–143. Biography Alice Butler is a PhD student at the University of Leeds, based in the School of Geography. She researches the production of territorial stigmatization and denigration, particularly in relation to the city of Liverpool. In addition, she is involved in research about the use and effects of the discourse of denigration on social media. Alice has a BA in French and Middle Eastern Studies and a MA in Politics. Andrew Rackley, British Library

This blog is a summary of sorts related to my current research for the British Sociological Association (BSA) and the British Library (BL). In it I discuss how I came to be here, why archives are more relevant to sociological research than they are often perceived to be, and start to address why documents and archives could play a more prominent role in the methodological canon. My background heavily involves documents. My mother was a librarian. My father made paper. I completed a B.A. in Ancient and Medieval History before qualifying and working as an archivist. So naturally my PhD focussed on the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. I am being flippant, of course. My principal concern was to understand what became of the documentary heritage: who was collecting material, why, and where to find it; what was termed the ‘knowledge legacy’ (Rackley, 2016). My thesis examined the interaction of actor and agency when documenting a ‘mega-event’; the main contention being that any such endeavour had to be active; supporting the notion that archives are not static containers of information or data waiting to be ‘discovered’ by researchers, but influenced by social forces. I am currently engaged as the BSA Fellow for Sociology at the British Library BL, a mouthful of a title, but one that encompasses the collaborative nature of my research, which aims to investigate why sociologists are (not) using archives, and what could be done to encourage a greater engagement between the two. An archive may be composed of books, papers, maps or plans, photographs or prints, films or videos and even computer-generated records that are ‘born-digital’. They are the past, present and future records, produced by people and organisations in their day-to-day activities. This includes governments, universities, hospitals, charities, professional bodies, families and individuals. These records are intended to be kept permanently, so the purpose of an archive is to both preserve the past and allow others to (re-)discover it. Following from this it is possible to say that archives are social constructs, they ‘are not natural but are culturally made’ (Gidley, 2017: 298). This is a key observation for the sociological relevance of archival content, and is an intrinsic part of contemporary archival theory. From the mid-1990s a particular train of archival thought has been to consider an archive as ‘always in the process of becoming’ (McKemmish in Reed, 2005: 128), essentially considering that the meaning of archival content is not fixed, but fluid; able to be (re)created and open to interpretation. Borrowing from the writings of Giddens, Upward (1996, 1997) conceptualised the ‘records continuum’ as an abstract conceptual model for interpreting the multiple actors and agencies that impact upon archives. Observing that Giddens’ writings on time-space distanciation provided a parallel to recognisable patterns in archives and records management, Upward firmly positioned the model as a window onto the multiple relationships and contexts a record can have across spacetime. Thus the ‘creation’, ‘capture’, ‘organisation’ and ‘pluralisation’ of content does not occur in isolation, or indeed in a linear fashion, but are concurrent and traceable to each instantiation of use (Upward, 2000). Such parallels are important to consider when using documents. Archives play a vital role in documenting and preserving individual, local, regional and national collective memories, which in turn serve to shape and reflect the identities and communities which they represent (Flinn et al., 2009; Ketelaar, 2008; Rackley, 2016). Archives do not exist in a vacuum, and archivists are no longer considered as independent, impartial custodians, just as the archives themselves are not thought to be the product of a passive accumulation of the historical record (Cook, 2013, Brothman, 2010). Rather, archivists have come to reflexively embrace the role which they play in creating the archival record and now recognise it as more of a social product. As either method or methodology, the use of archives and documentary sources does not feature prominently within sociological research primers, and where it can be identified it is often implicit and bereft of a consistent language with which it is discussed (Moore et al., 2017: ch5). The lack of an explicit methodology for archival research within sociology could somewhat explain the perceived lack of engagement with archives. Yet there are a growing number of sociological texts that bridge this gap (Stanley et al, 2013; Opotow and Belmonte, 2016), including most notably Moore et al’s (2017) The Archive Project. The crucial expression of the text for sociologists is in the recognition that ‘a widely held but misconceived assumption is that the documents that archives hold are always from and about ‘the past’…[however] many archives are organised around contemporary concerns and interests, while of course the contents of all archives are always read and understood within the present moment’ (Moore et al, 2017: ch1, section 1). Over the last few paragraphs I have discussed why I think archives are incredibly relevant to sociologists and what I perceive as a gap in sociological literature and methodology, in which documents and archival research are frequently overlooked. Aimee’s forthcoming (Grant, 2018) ‘how to’ guide – which I am quite excited to get my hands on – will be a welcome addition to the texts I have briefly included here. I was very excited when I learnt of the DRN and Aimee asked me to contribute to the blog as I felt we shared a similar vision: to engage researchers in conversation, build a corpus of related literature, and increase an awareness of, and engagement with, the fantastic resource embodied in archives and documents. The keystone of my project is a belief that there are many areas of the BL’s collections (and those of other archives) that have high value for the sociological community. As such, I hope the project will prove important to the BL and its users through promoting its content, and providing a richer understanding of the research potential of BL collections for sociologists in a manner that is useful to them. REFERENCES Brothman, B. (2010). Perfect present, perfect gift: Finding a place for archival consciousness in social theory. Archival Science, 10: 141-189. Cook, T. (2013). Evidence, memory, identity, and community: Four shifting archival paradigms. Archival Science, 13: 95-120. Flinn, A., Stevens, M. & Shepherd, E. (2009). Whose memories, whose archives? Independent community archives, autonomy and the mainstream. Archival Science, 9(1-2): 71-86. Gidley, B. (2017). Doing historical and documentary research. In Seale, C. (ed.) Researching Society and Culture. London: SAGE, 285-305. Grant, A. (2018). Doing EXCELLENT social research with documents: Practical examples and guidance for qualitative researchers. Abingdon: Routledge. Ketelaar, E. (2008). Archives as spaces of memory. Journal of the Society of Archivists, 29(1): 9-27. Moore, N., Salter, A., Stanley, L. & Tamboukou, M. (2017). The Archive Project: Archival Research in the Social Sciences. London: Routledge. Opotow, S. & Belmonte, K. (2016). Archives and social justice research. In Sabbagh, C. and Schmitt, M. (eds.) Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research. New York: Springer, 445-457. Rackley, A. (2016). Archiving the Games: collecting, storing and disseminating the London 2012 knowledge legacy. PhD thesis: University of Central Lancashire. Reed, B. (2005). Records. In McKemmish, S., Piggott, M., Reed, B. & Upward, F. (eds.) Archives: Recordkeeping in Society. Wagga Wagga, NSW: Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University: 101-131. Stanley, L., Salter, A. & Dampier, H. (2013). The work of making and the work it does: Cultural sociology and ‘bringing-into-being’ the cultural assemblage of the Olive Schreiner letters. Cultural Sociology, 7(3): 287-302. Upward, F. (2000). Modelling the continuum as paradigm shift in recordkeeping and archiving processes, and beyond: A personal reflection. Records Management Journal, 10(3): 115-139. Available online: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1108/EUM0000000007259 <accessed 10 January 2018> Upward, F. (1997). Structuring the records continuum part two: Structuration theory and recordkeeping. Archives and Manuscripts, 25(1): 10-35. Upward, F. (1996). Structuring the records continuum part one: Postcustodial principles and properties. Archives and Manuscripts, 24(2): 268-285. Biography Andrew Rackley qualified as an archivist from the University of Liverpool’s MARM programme in 2009 and completed a Collaborative Doctoral Award (2016) funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council working with the University of Central Lancashire, Preston, U.K. and the British Library. He has since worked as the Archivist on a Wellcome Trust project to catalogue and digitise the records of the Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead, at West Sussex Record Office, highlighting the pioneering reconstructive surgery received by members of the Guinea Pig Club from Sir Archibald McIndoe during the Second World War. He is currently employed as the BSA Postdoctoral Fellow for Sociology at the British Library. image © Barbara Ibinarriaga Soltero Barbara Ibinarriaga-Soltero, PhD student, Cardiff University Psychologist at UNAM, C.U.

“Hecho en C.U.” which means “Made in C.U.”, is an important phrase to express the identity attached to being either a current or an ex-student at National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in the main campus in Mexico City. Although the origin of this expression comes from the celebration of a football soccer player, Jaime Lozano, from the team Pumas UNAM (Espinosa Beltrán, 2005), it can take different subjective meanings and symbolism. In this case, “Made in C.U.” refers to my professional development as a Psychologist in this Alma Mater well-ranked in Latin America (QSWUR 2018). It also speaks for the historical relevance of the Central University City Campus of the UNAM recognised in the World Heritage Collection (UNESCO, 2007), and for its reference in its bibliographic collection, including more than 13 million titles sheltered in 135 libraries (Fundación UNAM, 2016) encompassing the Central Library (see image). My training as a Psychologist at UNAM involved a deep engagement with a positivistic perspective towards the study of mindfulness; that is, objectifying mindfulness as a quantifiable process or intervention from which changes in psychological process and behaviour could be measured and reported. This constituted the more accepted approach to study the topic which obeyed not only a disciplinary logic within psychology (i.e., looking at psychological processes as observable and assessable phenomena; Haig, 2014) but from the development within the scientific ground as a whole, presenting Mindfulness-based interventions backed with scientific evidence of its efficacy and applicability in different scenarios (e.g. from health and education to the workplace and the criminal justice system; see Mindful Nation UK, 2015). However, mindfulness within the social sciences has been investigated in many interesting ways (Ibinarriaga-Soltero, 2017). For instance, it has been used as a method towards psychosocial investigation (Stanley, Barker, Edwards, & McEwen, 2014), and some of the recent studies have looked at participants' subjective experience through first-person perspective methods (Stelter, 2009). This stream of research has been of academic interest for my doctoral research in three levels: epistemologically regarding the way of approaching the topic, not only as a researcher but as a practitioner (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2009), ontologically as to understanding mindfulness as a practice intertwined with social and cultural aspects of the individual (Stanley, 2012) and not solely to her or his cognitive process located in the brain as empathised by research in neuroscience, and methodologically relevant as to the research design and the methods widely employed to investigate and to comprehend widely mindfulness within a particular geographical, social, and cultural context such as Mexico. Why Archive Searches and Document Analysis? One of the challenges that my research has set up so far is the need of conducting archives searches and analysis of documents to historically understand how mindfulness and other meditation practices, which have their origins in Buddhist Philosophy from East Asian countries, have been imported and commodified (Hyland, 2015) in Western countries. These methods have been poorly used among psychologists and specifically within the field of mindfulness studies. In the case of my doctoral research, I see a parallel of the significance of archives and documents as sources in social science research and some of the Buddhist texts. For instance, the Pāli Canon which is considered the authoritative source of Buddha´s teachings (Bhikkhu Bodhi, 2005) which have been passed from generation to generation for more than 2,500 years now. These Buddhist records such as other types of documents such as meditation diaries, policy reports, records of conferences and events as well as constitutive acts of different organisations constitute sources for collecting data which eventually aid a deepening understanding of human life and historically situation the transformation of knowledge and practices in different societies. By attending the GW4 workshop 'Methodological approaches to document analysis in Social Sciences' offered at Cardiff University, I was introduced to a new perspective to frame my research. It wouldn´t be possible for me to go back to my former University Campus, UNAM C.U., and conduct an archives search without being immersed within the diversity of approaches and art of working with documents during the workshop. I remain thankful for the Documents Research Network for organising the training session, as it was the starting point to develop the pilot study I am conducting in Mexico City at the moment. This study considers a documents analysis as data collection plan to understand historically which main factors have influenced the appropriation of Buddhism and the implementation of contemplative practices in the Mexican context, which also includes identifying pioneers of this movement through the archives search. The phrase “Hecho en C.U” means to me not only an identity affiliation of the place where I started my training as a psychologist, but a starting point of my journey of searching archives and analysing documents - which potentially would influence and contribute approaches to mindfulness studies within the social sciences. References Alvesson, M. & Sköldberg, K. (2009). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research. (2nd ed.). London, England: Sage. Bhikkhu Bodhi. (Ed.). (2005). In the Buddha´s words: An anthology of discourses from the Pāli Canon. US: Wisdom Publications. Espinosa Beltrán, A. (2005, June). Hecho en C.U: De cómo los Pumas me devolvieron la identidad [Made in C.U: How the Pumas restored my identity]. Revista Digital Universitaria, 6(6), 2-7. Retrieved from http://www.revista.unam.mx/vol.6/num6/art56/jun_art56.pdf Fundación UNAM. (2016, November). Acervo bibliográfico de la UNAM: El más importante de América Latina [Bibliographic collection of the UNAM: The most important in Latin America]. Retrieved http://www.fundacionunam.org.mx/unam-al-dia/acervo-bibliografico-de-la-unam-el-mas-importante-de-america-latina/ Haig, B. D. (2014). Investigating the psychological world: Scientific method in the behavioural sciences. London, England: MIT Press. Hyland, T. (2015). The commodification of spirituality: Education, mindfulness and the marketisation of the present moment. PROSPERO: Philosophy for Education and Cultural Continuity, 21(2), 11-17. Ibinarriaga-Soltero, B. (2017, January-July). Atención consciente (mindfulness): Una mirada crítica [Mindfulness: A critical perspective]. Journal of the International Coalition of YMCA Universities (8th ed.), 5(8), 73-92. Retrieved from http://ymcauniversitiescoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Eighth-Journal.pdf Mindful Nation UK. (2015). The Mindfulness Initiative. Retrieved http://www.themindfulnessinitiative.org.uk/images/reports/Mindfulness-APPG-Report_Mindful-Nation-UK_Oct2015.pdf QSWUR (2018). QS World University Rankings: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Retrieved https://www.topuniversities.com/universities/universidad--autonoma-de-mexico-unam#wurs Stanley, S. (2012). Mindfulness: Towards a critical relational perspective. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(9), 631-641. Stanley, S., Barker, M., Edwards, V., & McEwen, E. (2014). Swimming against the stream? Mindfulness as a psychosocial research methodology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12, 61-76. Stelter, R. (2009). Experiencing mindfulness meditation—a client narrative perspective. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 4, 145–158. UNESCO. (2007). World Heritage List: Central University City Campus of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Retrieved http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1250 Biography: Barbara Ibinarriaga-Soltero is a PhD student in Social Sciences at Cardiff University. She graduated as a Psychologist from National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico City, where she first started practising mindfulness and conducted research on the topic. Organising and delivering workshops based on mindfulness, emotional regulation and body awareness for students and lecturers was part of her professional development before she moved to the UK to study her Master´s degree in Social Sciences Research Methods. Currently, her doctoral research focuses on the critical-historical study of the contemplative practices employed in Higher Education in Mexico and the different pedagogies attached to them. Source: http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/132286/fiore-furlan-dei-liberi-da-premariacco-combat-with-dagger-italian-about-1410/

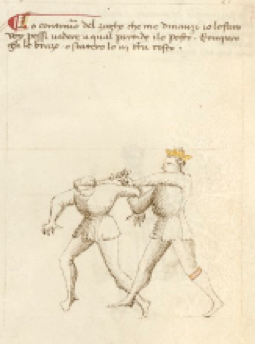

Daniel Jaquet, Castle of Morges and its Museums, Switzerland While readers of this blog are already familiar with transdisciplinary approaches relying on other data than mainly documents in their research, I would like to outline some of the avenues I have explored as an historian in the context of my research. I have been taught that documents are the main focal point of any research. As a medievalist, I cannot argue against this statement, although many trends in research are actually attempting to go “beyond documents”. Computer generated data, material culture, experimental data are all different ways used to shed new lights on documents. Here are some examples. The “Venice time machine” is reconstructing social networks with high technological scanning devices, processing big data out of one of the broadest archive in Europe[1]. HART (Historically Accurate Reconstruction Techniques[2]) is a new way of exploring art in the making for museum professionals and art historians. It opened new avenues and led to interesting projects based on the study of documents, such as the “Making and Knowing Project” in New York[3]. All of this being truly exciting, it does not, however, consider the complex variable of the body in the equation. My research on European martial arts of the 15th and 16th centuries is based on incredible documents: the fight books[4]. It deals with inscription, description or codification of martial knowledge on paper, whereas this media is imperfect for the task. Embodied knowledge, such as martial arts or dance, is indeed transmitted in a face-to-face situation, by oral means including demonstration, imitation, and correction. This is one of the many reasons why this document type is abstract, sometimes locked, to a 21st century researcher. I had to find ways to get beyond these documents, since it indeed raises highly relevant questions. That is, to cut the story short, why these authors actually attempted an impossible task? What does this tell us about the society and the status of martial arts back then? Even, can we actually learn how to fight according to their books? Many practitioners of “HEMA” (Historical European Martial Arts) train worldwide and even compete in martial arts considered to be “out of the book”[5]. If I am myself an HEMA practitioner, and I train for leisure; I do not focus my scientific work on finding how they fought, and, as a scholar, I do not care much about the study of modern-day HEMA. My hobby did nonetheless enlighten my research, but when it comes to scientific work, I focus more on how and why these books were written. However, before even trying to answer, I had to look into this material and find ways to understand it. The main issue in studying this kind of written or depicted embodied knowledge is to distinguish between explicit and tacit knowledge[6]. When tacit knowledge is identified, the reader lacking it need to find ways to reconstruct it. I started with looking into material culture to bridge the gap. Fight books concerned with martial techniques to fight an armoured opponent on foot or on horseback do not explain why and how the armour actually affected the body mechanics. The authors and its readers shared this knowledge, but it is lost to us. I then started a long path to go around the impossible task to go to a museum and take a suit of armour out of the display to wear it and to experience how it felt. While this was an uneasy path, it was very rewarding. I met movement scientists and energy expenditure specialists (University of Lausanne and Geneva) to actually document my experiment attempting to measure the impact of a fine replica on my body. I underwent 3D motion capture for gait and functional movement analysis and ran on a motorised treadmill to measure energy expenditure[7]. Out of this experience, I was then able to better understand these documents and to pursue my quest for answers. I do however understand that I cannot communicate on paper what I now know (even if I try hard), because the process of doing it actually provided me with more information than any reader would take out of reading the results of the experiment or any of my scholarly publication. To circle back to the beginning of this post, I would like to encourage scholars to explore unfamiliar paths to study documents. Some of the recent attempts on going beyond documents led to success stories (Venice Time Machine, Making and Knowing Project). However, when it comes to take embodied knowledge under the microscope, the documents reach their limits. New interesting questions are then faced, regarding both the study of ancient documents, and the new documents we are producing as scholars. Let’s explore new ways! Have a read to an interesting project of Dr. Benjamin Spatz willing to offer new platforms to communicate embodied research today (Journal of Embodied Research) and stay tuned for the publication of the first issue![8] References Abbot, Alison (2017). The ‘time machine’ reconstructing ancient Venice’s social networks. Nature, News Feature https://www.nature.com/articles/n-12446262 2. Carlyle, Leslie, and Witlox, Maartjee (2007). Historically Accurate Reconstructions of Artists’ Oil Painting Materials. Tate Papers 7. http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/07/historically-accurate-reconstructions-of-artists-oil-painting-materials 3. Making and Knowing Project http://www.makingandknowing.org/ 4. Jaquet, Daniel, Verelst, Karin, and Dawson Timothy, eds. (2016). Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. Leyden, Brill. http://www.brill.com/products/book/late-medieval-and-early-modern-fight-books 5. Historical European Martial Arts http://ifhema.com/ 6. Burkart, Eric (2016). Die Aufzeichnung des Nicht-Sagbaren. Annäherung an die kommunikative Funktion der Bilder in den Fechtbüchern des Hans Talhofer. in: Uwe Israel/Christian Jaser (Hrsg.), Zweikämpfer. Fechtmeister – Kämpen – Samurai (Das Mittelalter 19/2) https://www.academia.edu/25388370/Die_Aufzeichnung_des_Nicht-Sagbaren._Ann%C3%A4herung_an_die_kommunikative_Funktion_der_Bilder_in_den_Fechtb%C3%BCchern_des_Hans_Talhofer_in_Uwe_Israel_Christian_Jaser_Hrsg._Zweik%C3%A4mpfer._Fechtmeister_K%C3%A4mpen_Samurai_Das_Mittelalter_19_2_Berlin_2014_S._253_301 7. Jaquet, Daniel (2016).Range of motion and energy cost of locomotion of the late medieval armoured fighter: A proof of concept of confronting the medieval technical literature with modern movement analysis. Historical Methods 49/3. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01615440.2015.1112753 8. Journal of Embodied Research https://jer.openlibhums.org/ Daniel Jaquet Website: http://www.djaquet.info/ Daniel Jaquet is a medievalist (PhD in Medieval History, University of Geneva 2013), specialised in Historical European Martial Arts studies. He is the editor of the peer-reviewed journal Acta Periodica Duellatorum [add the link please: www.actaperiodicaduellatorum.com] and has recently co-edited: Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books (Brill, coll. History of Warfare 112, 2016). Tess Legg PhD student, University of Bath I attended the GW4 Document Analysis training day in Cardiff. I was really pleased to be able to be part of the day as I certainly agreed with the premise that, although research is increasingly being conducted using documents as data, there isn’t a lot of clarity around potential analysis techniques, nor the epistemological assumptions behind different methods.

I’m a 1 + 3 PhD student studying Health and Wellbeing at the University of Bath. I’m working within the Tobacco Control Research Group, investigating corporate influence on science. As Aimee Grant outlined in her presentation, tobacco control research is a site of much documentary analysis work. This is because of legal action in the US in the ‘90s which meant that millions of internal tobacco documents were made publicly available. The documents research that this led to has brought insights into the ways in which the tobacco industry has attempted to influence science, affect public discourse, and ultimately, influence policymaking decisions. My research is now looking at corporate influence on science and the use of science in policymaking more broadly, across different sectors (such as alcohol, fast food, and industries contributing to pollution and climate change). Documents will play an important role in my PhD, so this GW4 workshop was very relevant to the work I’ll be doing. Throughout the day I particularly welcomed discussion on the need to have greater specificity between analysis techniques, as I had found through previous reading that this could be a sticky issue. Of course there is often overlap between methods, but working out how they are distinct helps to pinpoint what exactly you want to do with your data, and how. The idea of ‘slow scholarship’ in science, which George Jennings introduced, is something which feels very topical. With researchers increasingly encouraged to think in ‘real time’ (through Twitter, etc.) and keep up with the speed of policymaking, it was good to hear George remind us all that science is a ‘marathon not a sprint’. Finding more time for reflection on our own perspectives and research findings remains important. This may be easier said than done in a busy world, however! As an interdisciplinary student working in a field where both realist and constructionist forms of research exist alongside each other, it was interesting to hear about Jonathan Scourfield’s oscillation between paradigms throughout his career. It seems that academics often have less linear career paths than it may first appear, so it’s great that people are happy to talk about that and shed some light on how they came to be working both on their particular subject areas and through particular paradigmatic lenses. Emilie Whitaker led us through a critical analysis workshop where we began to analyse a political speech, dissecting it to find underlying ideologies and rhetoric. I found Emilie’s lecture really helpful to understand that in this type of research, analysis techniques are not necessarily tied to particular epistemologies. For example, critical analysis of documents could be led by Marxist or feminist thought where the focus is on issues of hegemony. The same documents could be interpreted in any number of other ways, including through a Foucauldian lens where the focus may be more concerned with knowledge as power and how status is given to science, for example. Days like this are great as you get to talk to other PhD students about their research, discuss your own, and learn from experienced academics. I’m sure there would be lots of interest in more documentary analysis training. I’m looking forward to hearing more about the Documents Research Network, and have been spreading the word. Thank you to Maria, Fryni, Aimee, George, Emilie, and Jonathan for a great day! Clive Lee PhD student, University of Exeter The Methodological approaches to document analysis in Social Sciences workshop at the University of Cardiff was a watershed in my development as a professional doctorate studying at the University of Exeter and working at the University of Bath.

There was something about the workshop, and perhaps about my maturity as a doctoral student (I started in 2013, completed the pre-thesis stage in 2015 and am now working on the thesis), that meant I felt able to participate, and even contribute, at an event like this for the first time. So, what of document analysis and its relationship to my research? My supervisor suggested documentary analysis to supplement a predominantly autoethnographic study situated in my professional area, the teaching of English for academic purposes. Publicly-sourced documents, largely from the Internet, have three advantages for me: they play to the critical approach I aspire to, they enjoy the potential to circumvent some of the ethical issues inherent in my topic, and they offer the potential to both corroborate the evidence of my context and broaden its application. Dr Emilie Whitaker’s presentation on The critical turn: an introduction to the work of documents in political framing was what had attracted me to the workshop. I was not disappointed. It was both stimulating and inspirational to see critical research in action in a new context. Emilie’s practical session in the afternoon, analysing a David Cameron speech, and the discussion about how our insights could be presented academically gave me just the push I needed to start actually writing that part of my thesis. Ultimately, the presentations and the conversations helped me to realise that document analysis is an emerging methodology and that there are different ways to approach it. In this regard, I particularly liked Emilie’s English Language/English Literature analogy: the potential validity of a “literary” approach appeals to me in the context of my research. That said, Dr Aimee Grant’s Why documents are amazing and how they can be used in social research did provide a useful starting point methodologically. I was pleased I chose to go to Aimee’s session in the afternoon about infant formula marketing material to see this in practice, which again led to a helpful discussion about how such insights could be presented academically. Given that my research makes use of website material, Dr George Jennings’s presentation on Taking a slow look at “messy” documents: reflections from a decade of martial arts research was also very relevant. Looking at documents from a wider perspective that simply text is something I will be doing in my research. Finally, although not an academic point, another thing I took away from the day was its organisation. Thanks to Maria Pournara and Fryni Kostara for putting together a perfectly-paced day. I intend to make use of the pacing in my 2018 teacher induction week. Too bad 2017’s had already been fixed! |

AuthorMembers of the Documents Research Network Archives

June 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed