|

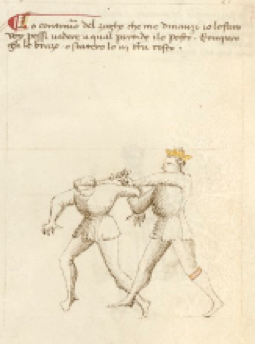

Source: http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/132286/fiore-furlan-dei-liberi-da-premariacco-combat-with-dagger-italian-about-1410/

Daniel Jaquet, Castle of Morges and its Museums, Switzerland While readers of this blog are already familiar with transdisciplinary approaches relying on other data than mainly documents in their research, I would like to outline some of the avenues I have explored as an historian in the context of my research. I have been taught that documents are the main focal point of any research. As a medievalist, I cannot argue against this statement, although many trends in research are actually attempting to go “beyond documents”. Computer generated data, material culture, experimental data are all different ways used to shed new lights on documents. Here are some examples. The “Venice time machine” is reconstructing social networks with high technological scanning devices, processing big data out of one of the broadest archive in Europe[1]. HART (Historically Accurate Reconstruction Techniques[2]) is a new way of exploring art in the making for museum professionals and art historians. It opened new avenues and led to interesting projects based on the study of documents, such as the “Making and Knowing Project” in New York[3]. All of this being truly exciting, it does not, however, consider the complex variable of the body in the equation. My research on European martial arts of the 15th and 16th centuries is based on incredible documents: the fight books[4]. It deals with inscription, description or codification of martial knowledge on paper, whereas this media is imperfect for the task. Embodied knowledge, such as martial arts or dance, is indeed transmitted in a face-to-face situation, by oral means including demonstration, imitation, and correction. This is one of the many reasons why this document type is abstract, sometimes locked, to a 21st century researcher. I had to find ways to get beyond these documents, since it indeed raises highly relevant questions. That is, to cut the story short, why these authors actually attempted an impossible task? What does this tell us about the society and the status of martial arts back then? Even, can we actually learn how to fight according to their books? Many practitioners of “HEMA” (Historical European Martial Arts) train worldwide and even compete in martial arts considered to be “out of the book”[5]. If I am myself an HEMA practitioner, and I train for leisure; I do not focus my scientific work on finding how they fought, and, as a scholar, I do not care much about the study of modern-day HEMA. My hobby did nonetheless enlighten my research, but when it comes to scientific work, I focus more on how and why these books were written. However, before even trying to answer, I had to look into this material and find ways to understand it. The main issue in studying this kind of written or depicted embodied knowledge is to distinguish between explicit and tacit knowledge[6]. When tacit knowledge is identified, the reader lacking it need to find ways to reconstruct it. I started with looking into material culture to bridge the gap. Fight books concerned with martial techniques to fight an armoured opponent on foot or on horseback do not explain why and how the armour actually affected the body mechanics. The authors and its readers shared this knowledge, but it is lost to us. I then started a long path to go around the impossible task to go to a museum and take a suit of armour out of the display to wear it and to experience how it felt. While this was an uneasy path, it was very rewarding. I met movement scientists and energy expenditure specialists (University of Lausanne and Geneva) to actually document my experiment attempting to measure the impact of a fine replica on my body. I underwent 3D motion capture for gait and functional movement analysis and ran on a motorised treadmill to measure energy expenditure[7]. Out of this experience, I was then able to better understand these documents and to pursue my quest for answers. I do however understand that I cannot communicate on paper what I now know (even if I try hard), because the process of doing it actually provided me with more information than any reader would take out of reading the results of the experiment or any of my scholarly publication. To circle back to the beginning of this post, I would like to encourage scholars to explore unfamiliar paths to study documents. Some of the recent attempts on going beyond documents led to success stories (Venice Time Machine, Making and Knowing Project). However, when it comes to take embodied knowledge under the microscope, the documents reach their limits. New interesting questions are then faced, regarding both the study of ancient documents, and the new documents we are producing as scholars. Let’s explore new ways! Have a read to an interesting project of Dr. Benjamin Spatz willing to offer new platforms to communicate embodied research today (Journal of Embodied Research) and stay tuned for the publication of the first issue![8] References Abbot, Alison (2017). The ‘time machine’ reconstructing ancient Venice’s social networks. Nature, News Feature https://www.nature.com/articles/n-12446262 2. Carlyle, Leslie, and Witlox, Maartjee (2007). Historically Accurate Reconstructions of Artists’ Oil Painting Materials. Tate Papers 7. http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/07/historically-accurate-reconstructions-of-artists-oil-painting-materials 3. Making and Knowing Project http://www.makingandknowing.org/ 4. Jaquet, Daniel, Verelst, Karin, and Dawson Timothy, eds. (2016). Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. Leyden, Brill. http://www.brill.com/products/book/late-medieval-and-early-modern-fight-books 5. Historical European Martial Arts http://ifhema.com/ 6. Burkart, Eric (2016). Die Aufzeichnung des Nicht-Sagbaren. Annäherung an die kommunikative Funktion der Bilder in den Fechtbüchern des Hans Talhofer. in: Uwe Israel/Christian Jaser (Hrsg.), Zweikämpfer. Fechtmeister – Kämpen – Samurai (Das Mittelalter 19/2) https://www.academia.edu/25388370/Die_Aufzeichnung_des_Nicht-Sagbaren._Ann%C3%A4herung_an_die_kommunikative_Funktion_der_Bilder_in_den_Fechtb%C3%BCchern_des_Hans_Talhofer_in_Uwe_Israel_Christian_Jaser_Hrsg._Zweik%C3%A4mpfer._Fechtmeister_K%C3%A4mpen_Samurai_Das_Mittelalter_19_2_Berlin_2014_S._253_301 7. Jaquet, Daniel (2016).Range of motion and energy cost of locomotion of the late medieval armoured fighter: A proof of concept of confronting the medieval technical literature with modern movement analysis. Historical Methods 49/3. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01615440.2015.1112753 8. Journal of Embodied Research https://jer.openlibhums.org/ Daniel Jaquet Website: http://www.djaquet.info/ Daniel Jaquet is a medievalist (PhD in Medieval History, University of Geneva 2013), specialised in Historical European Martial Arts studies. He is the editor of the peer-reviewed journal Acta Periodica Duellatorum [add the link please: www.actaperiodicaduellatorum.com] and has recently co-edited: Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books (Brill, coll. History of Warfare 112, 2016).

1 Comment

11/11/2019 03:06:20 pm

I do however understand that I cannot communicate on paper what I now know (even if I try hard), because the process of doing it actually provided me with more information than any reader would take out of reading the results of the experiment or any of my scholarly publication.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMembers of the Documents Research Network Archives

June 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed